M. Manola¹, L. Moscillo², A. Mastella², B. Ferrillo², G. Battiloro³, D. Lacerenza³

1 SC Interaziendale di Otorinolaringoiatria e Chirurgia Oncologica Maxillofaciale – ASP – CROB – Basilicata

2 UOC di ORL, Ospedale “S. Maria delle Grazie”, Pozzuoli (NA), ASL NA2 NORD

3 SC Interaziendale di Oculistica – ASP – San Carlo – Basilicata

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Chronic obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct leads to inflammation or infection of the lacrimal sac (dacryocystitis). The aim of the present study was to evaluate the clinical outcome of 128 endonasal endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy in 108 patients with epiphora or dacryocystitis.

Methods: 108 patients with nasolacrimal duct obstruction were recruited for the study (F/M ratio: 5:1, mean age: 55 years). Exclusion criteria were pre-saccal obstruction and malignancy in the paranasal sinuses. The minimum length of follow up was 12 months. All the procedures were performed by one otolaryngologist and one ophthalmologist.

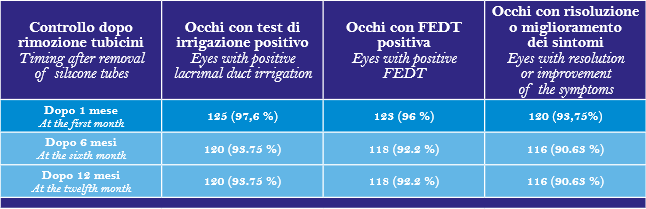

Results: The silicone tube removal was completed, on average, in 35 postoperative days. 44 patients had nasal surgery associated with endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy (36 septoplasty and 8 Endoscopic Sinus Surgery- ESS). After 12 months, symptomatic success was observed in 116 out of 128 eyes.

Conslusions: Authors’ findings, according to literature data, indicate that the classic endonasal endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy is a promising surgical technique both in terms of results and of postoperative morbidity

Keywords: dacryocystorhinostomy, endoscopy, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, epiphora, dacryocystitis

INTRODUCTION

Endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) was first described by Caldwell 1 in 1893; however, at that time the use of this technique was limited due to poor vision of the surgical field. Eleven years later, Toti 2 described the external DCR. This procedure has been modified over the years but it remains the gold standard for the treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction (NLD). Chronic obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct secondary to chronic inflammation leads to inflammation or infection of the lacrimal sac (dacryocystitis). The main symptom is epiphora, but the conjunctiva can also be inflamed and in some cases digital pressure over the lacrimal sac can extrude pus through the puncta. In the late 80’s, with the advent of endoscopic nasal surgery, the endonasal endoscopic approach to perform DCR became feasible. This technique was described for the first time by Rice3; McDonogh, in 1989, reported the first clinical study of endonasal endoscopic DCR4. The reported success rate of the endonasal DCR is very variable; it ranges from 63 to 95%5,6,7due to the fact that the technique is not standardized. To date the endonasal approach has not given the expected results as compared to the external approach, but the advantages of endonasal DCR over external DCR have made the former more popular in the past few years8. Furthermore in recent years the clinical results have also shown improvements. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the clinical outcome of 128 endonasal endoscopic DCR in 108 patients with epiphora or dacryocystitis.

METHODS

1128 primary endoscopic DCR with lacrimal intubation were performed at S. Giovanni di Dio Hospital, Melfi, Italy from June 2011 to January 2014 on 108 patients (90 females, 18 males) with acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction. 20 patients underwent bilateral procedure, while 88 patients had unilateral endoscopic DCR. 44 patients had a nasal surgery associated with DCR (36 septoplasty and 8 ESS). The patients were on average 55 years old. Patients were scheduled for surgery because of tearing or recurrent dacryocystitis. Exclusion criteria were pre-saccal obstruction and malignancy in the paranasal sinuses. The minimum length of follow up was 12 months, with average follow up of 24 months. All the procedures were performed by one otolaryngologist and one ophthalmologist. The pre-operative evaluation included an ophthalmological examination with lacrimal duct irrigation, fluorescein dye test (FEDT) 9 and endoscopy (rigid 0 °optic fiber with 0.8 mm of diameter and 10 cm of length) of lacrimal system as well as an ENT examination with nasal endoscopy (rigid 0° and 30 ° optic fiber with 4 mm of diameter and 18 cm of length). A CT was requested when a nasal pathology was found or suspected in 24 patients out of 108 (22.2%) The postoperative assessment included the anatomical and functional outcome: subjective recording of symptoms, nasolacrimal irrigation and FEDTrealized 1, 6 and 12 months after removal of silicone tubes The operation was defined as being successful if the patient was asymptomatic or the symptoms improved within 12 months.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The procedure was carried out under general anesthesia with an endoscope 0° or 30° The nasal mucosa was prepared with pledgets soaked in naphazoline 10% placed along the inferior turbinate, axilla of middle turbinate, middle meatus and over the mucosa overlying the maxillary line. Afterwards, mepivacaine 2% and adrenaline 1:100.000 was injected just above and anteriorly to the attachment of the middle turbinate and along the maxillary line. An incision was made with a sickle knife on the nasal lateral wall, starting 10 mm above the head middle turbinate, changing in a vertical incision 10 mm anteriorly the maxillary line for full exposure of the bone overlying the lacrimal sac and again horizontally until the inferior end of the uncinate process. With Freer elevator, a mucoperiosteal rectangular flap was raised until the uncinate process, so that it was possible to see the maxillary line and the thin lacrimal bone. When bleeding was settled, the bone overlying the lacrimal sac was removed making a large osteotomy (about 2cmx1cm) by a diamond burr of 2 -4 mm of diameter. In Authors’ experience, the outer upper limit of the osteotomy is where the probe, inserted in the canaliculi, runs horizontally without encountering bone in the nasal cavity and without the necessity of inclining it; or when the punctum of the common canaliculi is well visible. At this point, the sac was cut along its length in order to open it up and enlarged with a debrider. Silicone tubes are inserted through the inferior and superior canaliculi into the nose and tied. The mucoperiosteal flap was incised as a C shape and repositioned leaving the osteotomy open. A 4 cm nasal pack was positioned over the flap for 24 hours. A course of oral antibiotics, antibiotic-steroid eye drops and nasal irrigation with saline spray was given in the following 10 days. Debridement of the intranasal wound was included in the post-operative care. The silicone tubes were removed when the nasal mucosa was healed, on average in 35 postoperative days, with a maximum timeframe of 45 days after the operation.

RESULTS

The results are shown in table 1.The complication rate has been: in 4 patients a mild subeyelid hematoma; in 2 patients subeyelid subcutaneous emphysema; in 6 cases a mild nasal hemorrhage at the removal of the nasal pack requiring new nasal packing but without surgery; in 10 patients a postoperative nasal synechia. After 12 months, symptomatic success was observed in 116 out of 128 eyes that underwent endoscopic DCR (90.63%) while patency to syringing and a positive FEDT9,10in 120out of 128 (93.75%). There were no patients who reported symptomatic improvement but failed fluorescein testing. After 6 months every patient with complications had symptomatic success except in 4 cases with nasal synechiae.

DISCUSSION

The success of endonasal endoscopic DCR depends on various elements. The site of nasolacrimal obstruction seems to be a major factor influencing the final outcome. According to other Authors11, a better outcome is observed in patients with obstruction of the sac or nasolacrimal duct than in those with more proximal obstruction. The identification of the level of obstruction is critical in deciding the most proper management and medical care strategy. This can be detected with classical syringing of the canaliculi, endoscopy of the lacrimal system, dacryography and dacryo-CT. Syringing and dacryography generate high pressure during injection in the canaliculi and may mask an anatomic shrinkage of the lacrimal tract. Furthermore, Beige et al 12 concluded in their study that syringing of the lacrimal system may result in an inaccurate diagnosis (high false positive diagnosis) in patients with epiphora. Dacryo-CT allows evaluating functionally the lacrimal drainage system by injecting a contrast agent into the lower eye fornix and also provides information of the associated nasal pathologies. In Authors’ experience, endoscopy of the lacrimal system allows correct localization and direct visualization of the cause of epiphora, chronic inflammation, or dacryocystitis. Mucosal structure, scars and stenosis can be visualized and distinguished from debris and mucous secretions which can be easily removed. An endoscopy of the lacrimal system is a minimally invasive method that allows choosing the most appropriate surgical therapy CT scan is performed only in case of associated nasal pathology. Another significant factor that influences the outcome is the anatomy and pathology of the surround structures such as a deviated nasal septum, hypertrophic middle turbinate, nasal polyposis etc., that makes difficult the nasal approach to the sac. Also the conformation and the position of the sac in respect to the other structures can influence the outcome preventing the formation of an adequate lacrimal fistula and the possibility of an adhesion occurring between the middle turbinate or septum and the ostium of rhinostoma. Therefore, it is important to correct a nasal pathology in order to create the conditions for successful results. In the 12 patient with no improvement after 6 months, 6 had nasal polyps or sinusitis, 4 had nasal synechiae and 2 had unknown problems in scar tissue. The Authors consider, in the light of their results, that it is important to follow the patient after removal of the silicone tubes, because the healing process may lead to a worsening in both the symptoms and the results for up to 6 months postoperatively, while the results stabilize after six months (table 1).Another key point in the success of endonasal DCR is, in fact, the process of wound healing of the nasal mucosa. The precise mechanism is still unclear. Two phases are characteristics of the repair process: a regenerative phase and the stage of fibrosis8 . Some stimuli such as heat shock, laser, viral and bacterial infections, autoimmune response, chemical exposure, large rowing bone, may slow down the healing process or create granulation or abnormal fibrosis that prevents a correct wound healing13. Still controversial are some variations of the surgical technique such as flaps creation. Both Wormwald5 and Levine14 report a 95% rate of success when using flaps between nasal mucosa and sac mucosa; other Authors15 remove the medial wall of the lacrimal sac while others 16 use various types of laser to create the breach in the lateral nasal wall. As to the size of bony ostium, in some studies15, 17, 18 it is suggested to create an ostium that is large at least 1cmx1cm, while according to other Authors19 it is not necessary to create a large lacrimal fistula to obtain good results. It is still debated whether or not silicone intubation of the lacrimal passages should be used in endonasal endoscopic DCR. Silicone tubes can keep mucosal flaps in place or just maintain the patent rhinostoma until the healing is completed. However bi-canalicular tubing can cause production of granulation tissue and infections. In any case, there is general agreement to avoid leaving large row bony surface and to create a large bone window in the nasal side and to insert silicone tubes. Mann et al 20 demonstrated that there is no reason for prolonged intubation (> 4 weeks) to prevent rhinostomy closure. They described a reduction of the ostium size of 1.7 mm within four weeks. No reduction of the ostium size was demonstrated after this period. They concluded that the success rate with or without prolonged intubation is the same. The Authors remove the silicone tubes, on average, in 35 postoperative days.hey believe that the continued presence of silicone stents is not necessary and can cause granulations facilitating a recurrence of the issues. They don’t agree with Authors21,22 that consider intubation completely useless.

CONCLUSIONS

Endonasal endoscopic DCR in Authors’ experience has a 90.63% symptomatic success rate, and a 93.75% functional and anatomic success rate at the 12 month follow up. These are promising results in light of the fact that endonasal endoscopic DCR is a minimally invasive technique that avoids facial scarring, preserves the orbicularis oculi muscle pump function, allows a quicker recovery after surgery, and has little intraoperative bleeding and few complications when performed well7. Endonasal endoscopic DCR shows potential advantages and successful results and has turned out to be an accepted technique for the treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction23. In our study, by simply taking into consideration the objective dye test and patency to lacrimal syringing criteria, the endonasal endoscopic DCR was successful in 93.75% of the cases. The success rate is comparable to that reported by other Authors24,25 and very close to the external DCR results . The recent trend of the success rate of endonasal DCR in literature is closing the gap with external DCR, but it still falls short because the procedure itself is not standardized. Given the undeniable advantages and the excellent results, the endoscopic DCR should be considered the first choice treatment of nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

Table 1: lacrimal duct irrigation, fluoresceine dye test (FEDT) and improvement or resolution of the symptoms at 1, 6 and 12 months after removal of silicone tubes.

REFERENCES

1) Caldwell GW. Two new operations for obstruction of the nasal duct with preservation of the canaliculi. Am J Ophthlmol. 1893;189-92.

2) Toti A. Nuovo metodo conservatore di cura radicale delle suppurazioni croniche del sacco lacrimale. Clin Mod Firenze. 1904; 10: 385-9.

3) Rice DH. Endoscopic intranasal dacryocistorhinostomy: a cadaver study. Am J Rhinol. 1988;2:127-8.

4) Mc Donongh M, Meiring H. Endoscopic transnasal dacryocistorhinostomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1989; 103:585-7.

5) Wormald PJ. Powered endoscopic dacryocysthorinostomy. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:69-72.

6) Tsirbas A. Wormald PJ. Mechanical endoscopic dacryocysthorinostomy with mucosal flaps. Br. J. Ophthalmol.2003;87:43-7.

7) Anijer D, Dolan L, MacEwan CJ. Endonasal versus external dacryocysthorinostomy for nasolacrimal duct obstruction 2011 The Cochrane Collaboration. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

8) Goldberg RA. Endonasal dacryocysthorinostomy .Is it really less successful?. Arch Ophthalmol 2004;122:108-109.

9) Guzek JP, Yoon PS, Stephenson CB, Stephenson CM, Shavlik GW. Lacrimal testing: The dye disappearance test & Jones test. Annals of Ophthalmology. 1996;28:357-63.

10) Calkins LL. Lids, Lacrimal apparatus and Conjunctiva. Arch Ophthalmol. 1964;71:131-43

11) Yung MW, Hardman- Lea S. Analysis of the results of surgical endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: effect of the level of obstruction. Br J Ophthalmol 2002; 86: 792 – 794

12) Beige B, Uddin JM, McMullan TF, Linardos E. Inaccuracy of diagnosis in a cohort of patients on the waiting list for dacryocystorhinostomy when the diagnosis was made by only syringing the lacrimal system. Eur J Ophtalmol 2007 Jul-Aug 17(4) 485-9

13) Leong SC, Macewen CJ, White PS. A systematic review of outcomes after dacryocystorhinostomy in adults. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2010 Jan-Feb;24(1):81-90.

14) Levin B, Naganathan V, Amanda A, Ghabrial R. Endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy – an Australian perspective. Asian J Ophtalmol 2007;9(3):117-121

15) Sindwani R, Metson MB. Endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology 2008;19:172176.

16) Lee S, Yen MT. Laser-assisted dacryocystorhinostomy: a viable treatment option? Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2011;22(5):413418.

17) Moras K, Mahesh Bhat, Shreyas CS, Mendonca Norman, Pinto George External dacryocystorhinostomy versus endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: a comparison. Journal of clinical and Diagnostic Research 2011;5(2):182-186.

18) Zuercher B, Tritten JJ, Friedrich JP, Monnier P Analysis of functional and anatomic success following endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120(4):231238.

19) Sham CL, Van Hasselt CA. Endoscopic therminal dacryocystorhinostomy Laryngoscope 2000;110:1045-1049

20) Mann BS, Wormald PJ. Endoscopic assessment of the dacryocystorhinostomy ostium after endoscopic surgery. Laryngoscope. 2006 Jul;116(7):1172-4.

21) Smirnov G, Tuomilehto H, Teräsvirta M, Nuutinen J, Seppä J. Silicone tubing after endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: is it necessary? Am J Rhinol. 2006 Nov-Dec;20(6):600-2.

22) Unlu HH, Gunhan K, Baser EF, Songu M. Long-term results in endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy: is intubation really required?Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009 Apr;140(4):589-95.

23) Malhotra R, Wright M, Olver JM. A consideration of the time taken to do dacryocystorhinostomy (DCR) surgery Eye 2003;17:691-696

24) Karim R, Ghabrial R, Lynch TF, Tang B. A comparison of external and endoscopic endonasal dacryocystorhinostomy for acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction. Clinical Ophthalmology 2011,5: 879-989

25) Ben Simon GJ, Joseph J, Lee S, Schwarcz RM, McCann JD, Goldberg RA. External versus endoscopic dacryocystorhinostomy for acquired nasolacrimal duct obstruction in a tertiary referral center. Ophthalmology. 2005 Aug;112(8):1463-8.